Environmental health refers to the study of the role of environmental factors in public health. We will consider here the following questions:

(1) What do we mean by “environment” in environmental health?

(2) What are environmental hazards and risks?

(3) What is exposure and dose?

(4) What is Environmental Epidemiology and how is it related to Environmental Health?

(5) What is Environmental health risk assessment (EHRA)?

(6) How can we manage environmental health risks?

To begin with, we must be clear as to what we mean by the term “environment” when we talk of environmental health. We must know the difference between hazards and risks, as well as exposure and dose. How do we know that an environmental factor is harmful (or beneficial) for our health and what can we do about it?

One, we can conduct environmental epidemiological studies to test whether and to what extent an environmental exposure is beneficial or harmful for health;

Two, if we know of a hazard and it's associated health risk, then for a given group of people, we can conduct an environmental health risk assessment to characterise that risk for that particular group.

Also, if we were to know about how an environmental hazard is posing risk to human health, what can we do about it? What can we do to remove the hazard and protect human health?

We can use a framework to guide our action.

CONCEPT 1: WHAT DO WE MEAN BY “ENVIRONMENT” IN ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH?

By “environment” we mean any entity that is both:

(1) external to humans and

(2) results from human activities.

Consider cigarette smoking. Is cigarette smoke an environmental factor? Yes. Smoke from cigarettes results in air pollution; smoking is also associated with lung cancer and heart diseases among other illnesses. Cigarette smoke drifts in air and reaches our air passages as we inhale. Smoke results from human activities (smoking); smoke is external to us humans at the time it enters the body to cause harm; and, smoking harms our health. Hence smoking is an environmental health problem.

Now think of earthquake. Is earthquake an environmental health problem? No. First of all, earthquake is largely unpredictable (though there are latest technology now that helps to predict earthquakes but they are yet to be 100% in accuracy) and there is no reason to believe that earthquakes are results of human activities. However, earthquakes are associated with human health effects. There is some evidence that heart disease risk goes up following experience of earthquake. Kario et.al. (2003) noted,

Earthquakes provide a good example of naturally occurring acute and chronic stress, and in this review we focus mainly on the effects of the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake on the cardiovascular system. The Hanshin-Awaji earthquake resulted in a 3-fold increase of myocardial infarctions in people living close to the epicenter, particularly in women, with most of the increase occurring in nighttime-onset events

Source: Kario K1, McEwen BS, Pickering TG. Disasters and the heart: a review of the effects of earthquake-induced stress on cardiovascular disease. Hypertens Res. 2003 May; 26(5): 355–67. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12887126)

Because earthquake is a natural disaster, not a human engendered event, in spite of the health effect (heart disease), we’d consider it as a response to a natural disaster, not strictly an “environmental health” issue. It may seem that this distinction is pedantic, but it is not.

The critical element here is to decide whether something is “human engendered” or not. If you know something is “human engendered”, then you can think of a remedy or preventive action to mitigate the health effects as well.

This is important for prevention of health effects as if we can stop the generation of the harmful exposure by whatever action we may take, this will benefit public health. Sometimes the distinctions are fuzzy. For example, we know that increased frequency of storms and natural disasters are ascribed to global warming; you might as well argue that storms and natural disasters are more “environmental health” related events than “natural disaster related health problems”.

The pathway would be that human activities would result in increased greenhouse gas emissions; increased greenhouse gas emission is associated with increased temperature in the stratosphere by trapping infra-red radiation reflected from the earth surface and increase in carbon dioxide and methane trap heat; in turn these raise surface temperature on earth, increased ocean volumes and possibly changes in the patterns of wind flow around the equatorial region and results in increased frequency of natural disasters such as tropical storms (go and read “What is the link between hurricanes and global warming?”) How tropical storms have increased over time since 1985: is this natural or is there something more to it?

So, the term environment in environmental health points to the fact that humans are at one end of the chain of events that may lead to alteration of the environment. That alteration of the environmental conditions in turn lead to other events that affect our populations and health states. This connection is important.

CONCEPT 2: HAZARD VERSUS RISK: WHICH IS WHICH?

We are exposed to “agents in the environment” that can harm our health. The particulate matters in the air we breathe, the various chemical and biological contaminants in the water and food we consume, and almost everywhere and in all our activities through many other sources we are exposed to substances that can harm our health. Although all of these are “potentially” harmful, at any point in time, some of us are healthy, and some of us are ill. Any entity in the “environment” that can potentially harm our health is referred to as a “hazard”.

Think of a glass of water (about 300 millilitres)”.

A glass of water: harmful? beneficial?

Consumed in normal quantities of say 1.5 litres every day for a healthy person, water not only harmless, we need water to lead a healthy life. Yet if you were to consume say 3 litres of water per day, you might end up with symptoms of overhydration and damaging your kidneys. Here, water can be both healthful and harmful, depending on the amount we consume. This concept, that a substance that can be BOTH harmful and beneficial depending on the amount consumed is a significant point in environmental health and in “toxicology”, the study of toxins.

Aurolius Parcelsus (1493–1541) proposed that the dose is the poison

The Swiss German philosopher Aurolius Parcelsus (1493–1541) stated that the dose is the poison (sola dosis facit venenum) — a statement that forms the basis of toxicology. Everything can be hazardous. A pothole in the ground can be hazardous as a person who falls in the hole can injure himself; air can be hazardous if people inhale the toxic particulate matters; water can be hazardous if people drink too much, or if people fall in a pool. These are hazards in the sense of the potential that they can cause harms to humans. Thus HAZARDS are qualitative statements, and we consider any entity as a hazard if we can argue that they have a potential to cause harm.

In comparison to hazards, RISK refers to a quantitative statement where we ask, “after the hazard has been realised, what is the result?” This distinction is important. Cigarette smoke can harm our lungs; therefore smoke is a hazard. But the risk of cigarette smoking is lung cancer (among other diseases) and we can state that risk only after we find evidence that cigarette smoking is associated with lung cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, “Smoking shortens male smokers’ lives by about 12 years and female smokers’ lives by about 11 years”. This “shortening of life” is a statement of risk. Here, smoking is the hazard and the association of how it shortens people’s life is the statement of risk.

CONCEPT 3: EXPOSURE AND DOSE

The third concept in environmental health is the difference between EXPOSURE and DOSE. Environment in environmental health refers to those elements in our external environment that are caused by human activities, and that these entities are hazards in the sense that they can cause harm to our health; when they do harm our health, we can quantify the risks.

But in order that the hazards can lead to risks, we need to be “exposed” to the “hazards”. For polluted air to end up in health risks such as pneumonia, our lung tissues must be in “contact” with contaminants in polluted air; if we do not come in contact, or if we can break the contact with the pollutants, then the health effects will not result.

If we wear protective devices to keep out the contaminants or if we can take other precautions to keep out the contaminated air, then although the air is hazardous, we will be safe as we are not “exposed” and the risk will not accrue.

Exposure, therefore as you can see, like hazard, is a qualitative concept. The quantitative concept of exposure is dose. Think about drinking a glass of contaminated water. Does that mean that person will immediately suffer from harm? No, unless the “contaminants” in the water somehow “reaches” inside the body and interacts with the linings of our gut, then cross the gut epithelium, or act on the gut tissue and cause harm.

The amount of the contaminant that comes in contact with the body tissue on which it acts and gets to act is referred to as the “DOSE”. If the dose is low, even with exposure, the harm may not occur, so the hazard will not result in risk. Note that the phenomenon that a toxin or poison or a hazardous substance comes in “contact” with humans refers to the phenomenon of “exposure”; after the entity enters the human body following exposure, and reaches the target organ, the amount that reaches the target organ to cause harm refers to “dose”.

Dose therefore refers to the amount of the toxin that reaches the target organ ready to exert its effect. So, the pathway goes something like this:

hazard is present in the environment → we are exposed through an exposure pathway → dose of the hazard inside the body comes in contact with the tissues → exerts its action → the body acts on the hazardous object or its transformed products → health effects accrue (0r the body responds) → the risk

As we see in the above pathway, a hazardous object in the environment enters the body through exposure pathways, and exerts an effect on the tissue(s) when sufficient quantities of it accrue or are present. Speaking of biochemical or biological agents, this exertion of the hazard on the body by affecting body tissues is referred to as TOXICOKINETICS of the exposing agent.

The body, in turn, acts on the hazard and will modify or excrete or eliminate from the body. The action of the body on the hazardous object is referred to as TOXICODYNAMICS of the body on the agent. A balance between the toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics of the agent and the body on each other will determine how much of the toxic agent can exert its action on the body and how much the body can act to nullify it or remove it from the body and the net result is the health effect.

CONCEPT 4: ENVIRONMENTAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

So far, we have seen that anything in our external environment can be a hazard (or health hazard); the health hazard enters the body through one or more exposure pathway(s) and exerts its action on the body to result in health effects. But how do we know in the first place an agent in the environment is a health hazard?

How would we know that contaminated air or water or food that we have consumed has resulted in disease? How much of all diseases can be attributed to environmental variables? You can answer such questions by conducting Environmental Epidemiological studies. Environmental epidemiology refers to the study of distribution of diseases in populations where the determinants of such diseases are environmental.

As we move from hazard to risk, we traverse two paths that are serially linked: first, we must identify the hazard and second, we must characterise the risk. Think of a slippery pavement. We identify this to be a hazard to health: people can slip on a slippery pavement and break their hips (if slippery pavement is a hazard, then hip fracture is the risk of walking on a slippery pavement).

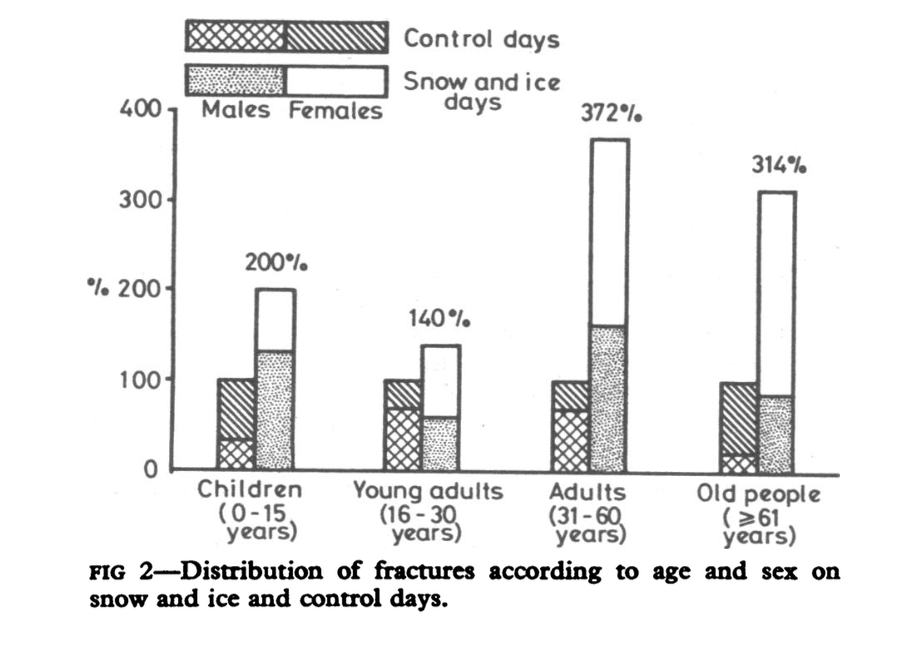

But how much of a risk is associated with a slippery pavement? Ralis (1981) conducted a study on icy pavements and risk of hip and other bone fractures in Cardiff, Wales in 1981; he studied patients who reported with fractures resulting from fall from walking on icy pavements on days when it snowed and compared it with what he termed as control periods or chosen days when it did not snow and calender days a year later. An illustrative graph shows the results:

Risk of fracture in icy days, from: Ralis, Z. A. (1981). Epidemic of fractures during period of snow and ice. BMJ, 282(6264), 603–605.

From this graph we see that for adults 31–60 years, snow and ice days had 272% more fractures that were reported to the hospitals than that in the control days (sunny days and days when they did not have snow and ice). For people aged 61 years and above, you can see that 214% more fractures were reported in the snow and ice days. These figures suggest that snow and ice days that result in icy pavements are risk factors for hip fractues and therefore icy pavements are hazardous to health. You may wonder what makes this an environmental epidemiological study if snow and ice storms cannot be human engendered. Can you think of how the human element in modification of environment comes into consideration of how people can slip and fall on icy pavements?

In any case, enviromental epidemiological studies like this enable us to move from conceptualisation of a hazard (slippery pavement) to actually identifying the risk of hip fracture. While icy pavement is considered a health hazard as presence of hard ice on footpath can be so slippery that anyone can fall, but the risk still needs to be quantified. It is “environmental” in the sense that if precaution to remove the ice would have been taken, then it might prevent the falls, and the human error in letting the ice on pavement makes these environmental hazard in the first place.

To recapitulate, epidemiology is defined as the study of the distribution and determinants of health related states and use of this knowledge for prevention of illnesses and for advancement of health (health promotion). In the context of environmental epidemiology, we specifically look at environmental factors as exposure and we compare people with and without specific health states or people with and without specific exposure and then compare exposure or health states.

Based on the findings of the studies we build the evidence on the linkage between environmental factors and health effects. Therefore understanding principles of epidemiology is critical for environmental and occupational health in testing explanations and theories that underlie the observations we make.

For example, in 1980s, doctors in the West Bengal state of India observed many patients who reported to them with signs of dark and white pigments in their palms and on their hands. Many of these patients were people who worked in farms and had for years consumed water they pumped from shallow tubewells (see the following figure):

Dark and light pigments in the hands and lesions or wounds in the hands/palms.

These are caused due to exposure to arsenic, source: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/arsenic/images/full_arsenic_pic7.jpg

The doctors suspected that the patients who reported to them with these lesions must have been exposed for a long time to inorganic arsenic, and to confirm their diagnoses, they ordered urine tests for these patients. As they suspected, urine samples tested positive for inorganic arsenic for these patients. But where was the arsenic coming from? Public health researchers considered that contaminated tubewells might be source from where the villagers were drawing water; they could be the source of arsenic in their water supply as these shallow tube wells were responsible for drawing up water from the aquifers that were contaminated with inorganic arsenic.

The researchers also compared the levels of inorganic arsenic in the drinking water of those people who had skin diseases and who did not have skin diseases using an epidemiological study design referred to as “case control study”. They found that people who had skin diseases had higher levels of inorganic arsenic in their drinking water, and the higher the concentration of inorganic arsenic, the higher was the likelihood that these people would end up with arsenic caused skin lesions. From these and other related investigations, they identified that inorganic arsenic was the cause of these skin lesions among these farming and rural community inhabitants, and established programmes to reduce or eliminate arsenic from the drinking water.

This is an example of an epidemiological study where the investigators started with people with illnesses or diseases and figured out the source or the cause of the disease. Epidemiological study designs can also be cross-sectional, meaning study designs where epidemiologists measure exposure and outcomes at the same time.

Other study designs are case-control study designs, where individuals with and without diseases are investigated for their likelihood of exposures. Cohort studies are epidemiological studies where people are “stratified” on the basis of their exposure status and are followed up over time to investigate what proportion of people in each arm (exposed versus non-exposed arms) develop the disease under study. These study designs are referred to as “observational study designs”.

Other than these study designs, epidemiologists also use ecological study designs where aggregates of environmental exposure statistics are compared with statistics of diseases. For example, concentration of air pollutants are compared for those with respiratory or heart disease related hospitalisations to test the association between air pollution and risk of heart disease related hospitalisation or asthma related hospitalisations.

CONCEPT 5: ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT

So far we have discussed issues around “environment” in “Environmental Health”, exposure, dose, hazards, risk, and Environmental Epidemiological studies. To recap,

Environment in Environmental Health refers to any change or any impact that human activities have on external environment. For example, burning of fossil fuels leads to air pollution; driving a vehicle that emits petroleum combustion products also leads to air pollution; use of a cooling refrigerant at home leads to emission of inert gases that tend to stay in the stratosphere for a long period; trans-pacific and trans-atlantic jet flights were associated with depletion of stratospheric ozone layers; use of plastic leads to pollution of land and oceans. All of these lead to environmental pollution or environmental contamination that in turn have health effects.

Hazard is the presence of any entity in the environment that can potentially affect human health.

Risk is the quantification of the health effects as an exposure to the environmental contaminant or the environmental hazard.

Exposure is the pathway or mechanism or phenomenon that we as humans or other animals or plants are opened ourselves up to the hazard. We are “exposed” to the potential hazards in many different ways.

Dose refers to what happens once we are exposed and the hazardous entity enters human body. Following entry human bodies can affect or impact the hazardous entity in many ways; likewise, the hazardous agent can in turn act on the human body. In either process, the cumulative effect results in the accumulation of agents in quantities that can harm our health or change our health status. This quantity is referred to as “dose”.

Environmental epidemiological studies are studies or research processes or knowledge processes by which we identify that X is a hazard. We start with health effects and construct the linkage between a supposed hazardous agent (often referred to as “putative hazardous agent”) and the health effect in question. For example, if we suspect that inorganic arsenic in drinking water is a hazardous agent that is responsible for skin diseases, then we need to conduct epidemiological studies to establish the linkage between exposure to inorganic arsenic in drinking water and appearance of skin lesions. The process by which such linkages are established or we establish that linkage is conduct of an epidemiological investigation.

In this section, we will turn our focus on what happens when we already know that X is a hazard to which a group of individuals are exposed. What do we do, or how do we establish the linkage between exposure to the hazard and quantify the risk? That process is referred to as “Environmental health risk assessment”. You can conduct Environmental health risk assessment by taking the following four steps:

Identify the hazard (Step 1, “Hazard identification”). Begin here.Then assess the exposure or how much of the hazard people you are working with are exposed to (Step 2, “Exposure Assessment”). The exposure assessment not only is about accruing knowlege about the exposure but also about knowing what happens when the exposed object or entity enters the human body: this is where we need to be aware of the toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics.

Simultaneously assess the dose response relationship (Step 3, “Dose Response Assessment”). We assume that it is the dose that is responsible for the risk. So higher the dose of an agent at the point of action in the body, the more intense will be the outcome, and hence important for risk.

If we know the extent to which a person is exposed to the hazardous agent, or entity, and if we know the nature of the dose response curve or dose response relationship, then we can ascertain the or we can characterise the risk (Step 3. “Risk Characterisation”).

This four-step process is referred to as “Environmental Health Risk Assessment” where we identify an environmental health hazard, and proceed in the four or three step process to move from identification of the hazard to characterisation of the risk associated with the hazard. For example, we know that emissions from factories and cars, and burning of fossil fuels will lead to particulate matters and gases that will harm our health. This is the step of identification of hazards.

Often such identification can be inferred from studies in human tissues; other times from animal experiments. Once a health hazard is identified, then the next step is to ascertain how much of it we are exposed to in our environment. For example, daily measurement of air quality is an indicator of how much of the air pollution we are exposed to on a daily basis. This step is referred to as “Exposure Assessment”. The exposure is not only on the outside environment, but also on the basis of molecules or compounds that we believe will accrue as a result of the exposure. For example, in case of air pollutants, we can sample from inhaled air how much of the particulate matters enter the body. In step 3, we ascertain the dose-response relationship.

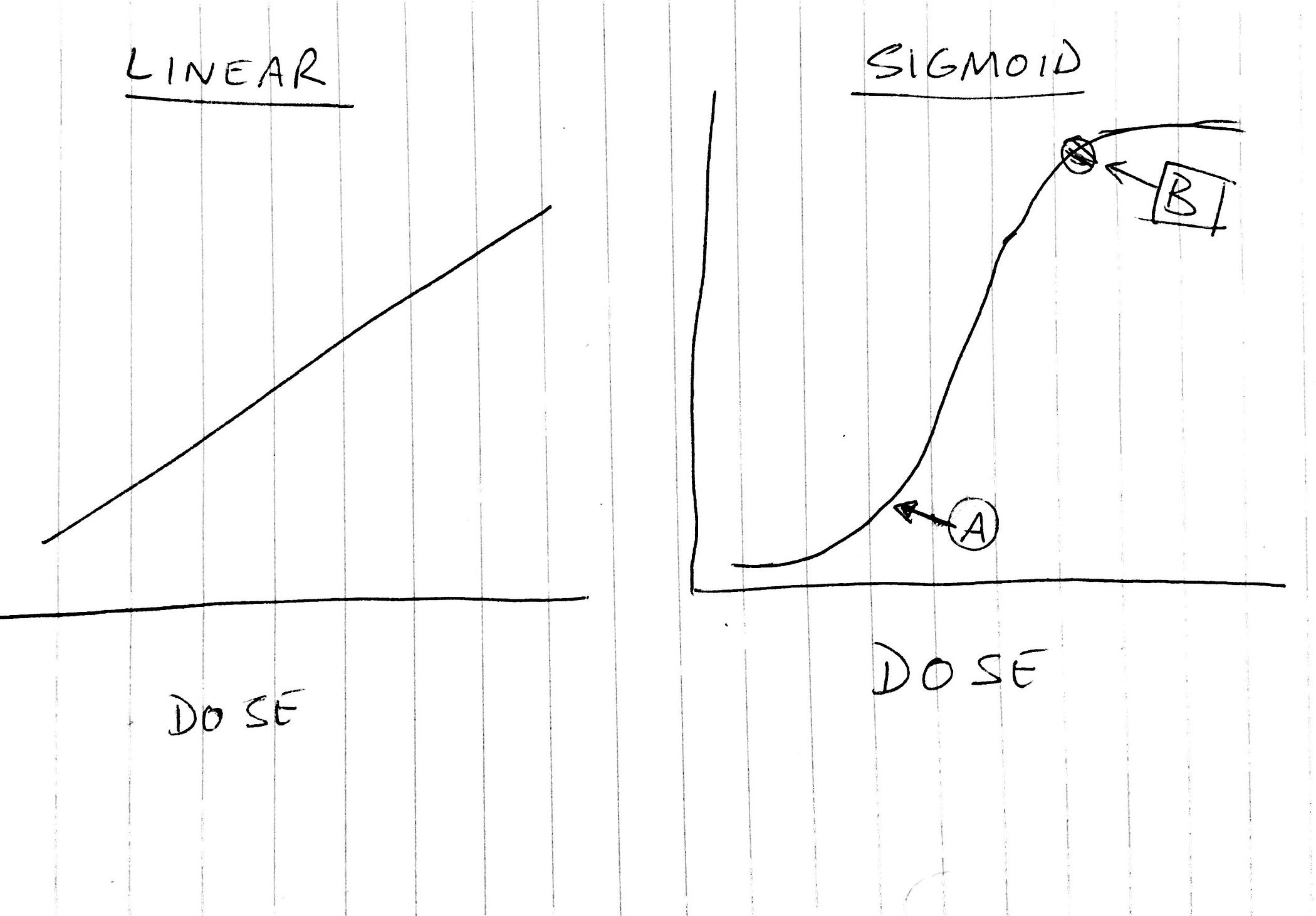

We assume as dose of the exposure increases, so does the likelihood of “effect” or health effect. The relationship can be linear, but it can also be in the form of a non-linear curve. For example, in the left hand side of the two figures below, we see a linear relationship between the dose and response of an agent. On the right hand side, we see a sigmoid shape of the curve. On the left hand side, we can infer that the dose will increase, so will the effect and we can predict using a linear equation. On the right hand side, the relationship is more complex. As the rate of increase in the effect will be slow to start with (lower end of the curve up to point A) and in the middle (between A and B), the rate of increase in the effect with respect to the dose looks like linear, but after a certain threshold level of the dose is reached (point B), the relative increase in the effect will be slower or flatter. This curve is referred to as sigmoid curve.

If we know the level of exposure (that is if we can ascertain how much we are exposed to the hazardous agent) and the nature of the dose response curve, then we can characterise the risk that will accrue as a result of exposure to the hazard for the dose levels. Environmental Health Risk Assessment (EHRA) is important for us to frame policies and arrive at decisions as to which toxic agents need to be treated in what order and how to protect maximum number of people.

CONCEPT 6: HOW DO WE MANAGE ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH RISKS?

The final concept is what do we do if we know about health risks from specific environmental and occupational hazards, or about management of environmental health risks? Given the many established (well known) and emerging health risks and environmental hazards that are already present, we need to think and devise ways in which we can minimise the hazards and mitigate the risks so that we can protect health of the public. Using frameworks allows us to respond to such challenges.

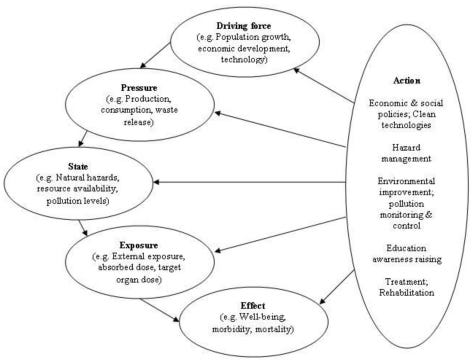

Frameworks provide a plan of action and a deeper understanding of some of the core issues that give rise to these situations in illnesses, and also provide a pathway in which we can integrate all our lessons we learn from epidemiological investigations. A framework that we shall discuss here is the DPSEEA framework (“Driving force — Pressure — State — Exposure — Effect — Action”).

The DPSEEA framework.

Driving force refers to those “forces” in the environment that has led to the emergence of the hazard. As in environmental health we mean human engendered actions as “environmental factors”, that concept of environment is also our “driving force”. Think of the different ways we as humans have altered our physical environment and the changes we drive. Some examples might be use of technology and producing wastes, fossil fuel usage and emissions, plastic waste. The “driving forces” that change the environment put “pressure” on the environment (think of these as downstream effects of all activities that we commit in step 1 or D). For example, we can contaminate the air using vehicle emissions only so much, beyond which it will be unsustainable for life.

Each time we put “pressure” on the environment, these pressures change the “state” of the environment. For example, as a result of population growth, we need to find housing for people, and therefore we encroach a forest and decide to cut it down the forest. When we do so, the “state” of the environment changes. You can see that overpopulation is our driving force, and we put pressure on the environment by destroying forests.

These activities and destruction of forest will expose us humans (and indeed every other living being in the forest as well) to several hazards, including: attack from animals who used to live in the forest, sound and noise pollution, vehicular traffic, worsening air quality of the region, soil erosion, water utilsation, waste disposal. Such exposures will exert their effects on public health.

Once you recognise the driving forces, pressures they exert on the environment, the state change that results from the forces, the exposure that results from that change of state, and the health effects that result from the exposure — these in turn invoke the action and the strategy you will take to mitigate the health effects. This is the ‘action’ (A of DPSEEA).

Where can you start? What options do we have? We can we do about it? At the outset, our aim is to reduce the exposure so that the health effects are minimised. But we should go upstream if we could, and reverse the state or change back to the original state, but this may not be possible at all times. Yet at other times, we may think of reducing or eliminating the pressure that driving forces exert. DPSEEA framework would behoove that we can and probably should start looking at this issue right from the D part of it (the driving forces).

A related concept is “precautionary principle’ where we should take action even if we are not certain of the mechanism of health effects certain exposure exert. For instance, if we were to know from our epidemiological studies and from environmental health risks assessment that indoor smoking was associated with pneumonia, then adopting the precautionary principle would make us reduce household air pollution or indoor air pollution in order to reduce the burden of pneumonia from that source.

Conclusion

In summary:

Environment in Environmental health refer to human engendered sources of alteration of our surroundings that in turn would affect our health. While there are other sources such as genetic or natural causes that could also impact our health states, environmental health would only refer to the human-caused changes in our “environment” that would affect our health states. This distinction is needed as in public health, our aim is to promote health and prevent illnesses. If we were to identify the root cause as human activities, then this knowledge would provide us with a way to address the root cause of the health problem.

Any entity in the environment (that conforms to the definition of environmental health) that is capable of causing harm to our health is termed as hazard. This concept of hazard is qualitative. Once we identify a hazardous entity in the environment, we can avoid it.

However, human illnesses or health states that occur as a result of interaction with the hazardous entity is risk, and risk is always quantified.

Interaction with the hazardous entity occurs in two phases:

(1) We would need to come in direct “contact” with the hazard or be opened up to the hazard: a state we call “exposure”, so we will have to be “exposed” to the hazard and

(2) After we are exposed, a certain amount or level of the exposing agent must be in contact with our tissues or selves so that it can exert its action. That amount or level is referred to as “dose”. The “dose” is the poison according to a fundamental concept of toxicology.

The hazard and the dose and the responses to the dose of exposure are studied using Environmental Epidemiology.

Environmental epidemiology is that branch of epidemiology where the determinants are in our environment. Many different study strategies are adopted by the environmental epidemiologists to identify, qualify and quantify hazards and risks: ecological studies, case series or surveillance, cross sectional surveys, case control studies, cohort studies, and intervention research such as randomised controlled trials.

If we know the hazards, then for communities and workplaces, we can conduct environmental health risk assessment.

This is a four step process where

(1) We identify the hazard in the first place,

(2) We measure the level of exposure and the dose that humans come in “contact” with the exposure or hazard,

(3) Ascertain the relationship between the dose and the associated health effect and

(4) Characterise the risk as to how many individuals are at risk.

If we know the hazard, the exposure route, the health risk, then it behooves us to mitigate the risk. This is best done by frameworks, and DPSEEA (driving force, pressure, state change, exposure, effects and action) is a framework that enables addressing the environmental health problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We need your feed back on our topics please